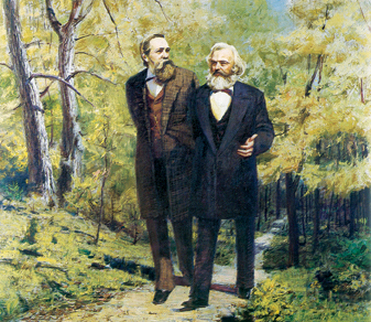

Frederick Engels on the Mind and Environment

By Adrian Chan-Wyles PhD

‘In short, the animal merely uses its environment, and brings about changes in it simply by his presence: man by his changes makes it serve his ends, masters it. This is the final, essential distinction between man and other animals, and once again it is labour that brings about this distinction.

Let us not, however, flatter ourselves overmuch on account of our human victories over nature. For each such victory nature takes its revenge on us. Each victory, it is true, in the first place brings about the results we expected, but in the second and third places it has quite different, unforeseen effects which only too often cancel the first. The people who, in Mesopotamia, Greece, Asia Minor and elsewhere, destroyed forests to obtain cultivatable land, never dreamed that by removing along with the forests the collecting centres and reservoirs of moisture they were laying the basis for the present forlorn state of these counties. When the Italians of the Alps used up the pine forests on the southern slopes, so carefully cherished on the northern slopes, they had no inkling that by doing so they were cutting at the roots of the dairy industry in their region; they had still less inkling that they were thereby depriving their mountain springs of water for the greater part of the year, and making it possible for them to pour more furious torrents on the plains during the rainy seasons. Those who spread the potato in Europe were not aware that with these farinaceous tubers they were at the same time spreading scrofula. Thus at every step we are reminded that we by no means rule over nature, and exist in its midst, and that all our mastery of it consists in the fact that we have the advantage over all other creatures of being able to learn its laws and apply them correctly.

And, in fact, with every day that passes we are acquiring a better understanding of these laws and getting to perceive both the more immediate and the more remote consequences of our interference with the traditional course of nature. In particular, after the mighty advances made by the natural sciences in the present century, we are more than ever in a position to realise and hence to control even the more remote natural consequences of at least our day-to-day production activities. But the more this progresses the more will men not only feel but also know their oneness with nature, and the more impossible will become the senseless and unnatural idea of a contrast between mind and matter, man and nature, soul and body, such as arose after the decline of classical antiquity in Europe and obtained its highest elaboration in Christianity.’

Marx – Engels: Selected Works in One Volume, Lawrence and Wishart Ltd, (1973), Page 362. This book was originally published by Progress Publications, Moscow, USSR (1968). This extract is quoted from the text entitled ‘The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man’ – written by Frederick Engels in 1876 during the lifetime of his friend Karl Marx. In 1862, Karl Marx wrote the following in a letter to Frederick Engels: ‘Darwin provides a basis in natural science for the class struggle in history.’ Although Engels quite rightly takes credit for writing the above text it is highly likely that he involved Marx all the way through its construction.

Let us not, however, flatter ourselves overmuch on account of our human victories over nature. For each such victory nature takes its revenge on us. Each victory, it is true, in the first place brings about the results we expected, but in the second and third places it has quite different, unforeseen effects which only too often cancel the first. The people who, in Mesopotamia, Greece, Asia Minor and elsewhere, destroyed forests to obtain cultivatable land, never dreamed that by removing along with the forests the collecting centres and reservoirs of moisture they were laying the basis for the present forlorn state of these counties. When the Italians of the Alps used up the pine forests on the southern slopes, so carefully cherished on the northern slopes, they had no inkling that by doing so they were cutting at the roots of the dairy industry in their region; they had still less inkling that they were thereby depriving their mountain springs of water for the greater part of the year, and making it possible for them to pour more furious torrents on the plains during the rainy seasons. Those who spread the potato in Europe were not aware that with these farinaceous tubers they were at the same time spreading scrofula. Thus at every step we are reminded that we by no means rule over nature, and exist in its midst, and that all our mastery of it consists in the fact that we have the advantage over all other creatures of being able to learn its laws and apply them correctly.

And, in fact, with every day that passes we are acquiring a better understanding of these laws and getting to perceive both the more immediate and the more remote consequences of our interference with the traditional course of nature. In particular, after the mighty advances made by the natural sciences in the present century, we are more than ever in a position to realise and hence to control even the more remote natural consequences of at least our day-to-day production activities. But the more this progresses the more will men not only feel but also know their oneness with nature, and the more impossible will become the senseless and unnatural idea of a contrast between mind and matter, man and nature, soul and body, such as arose after the decline of classical antiquity in Europe and obtained its highest elaboration in Christianity.’

Marx – Engels: Selected Works in One Volume, Lawrence and Wishart Ltd, (1973), Page 362. This book was originally published by Progress Publications, Moscow, USSR (1968). This extract is quoted from the text entitled ‘The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man’ – written by Frederick Engels in 1876 during the lifetime of his friend Karl Marx. In 1862, Karl Marx wrote the following in a letter to Frederick Engels: ‘Darwin provides a basis in natural science for the class struggle in history.’ Although Engels quite rightly takes credit for writing the above text it is highly likely that he involved Marx all the way through its construction.

©opyright: Adrian Chan-Wyles (ShiDaDao) 2016.